According to the World Health Organization, World Tuberculosis Day is marked every March 24, on the day in 1882 when Dr. Robert Koch announced that he had found the cause of tuberculosis, the TB Bacillus. According to the WHO site, at the time “TB was raging through Europe and the Americas, causing the death of one out of seven people.”

Once I saw that statistic, I understood more clearly why Peter H. Bryce had decided to pursue public health over neurology. He had studied in Paris with some of the pioneers of neurology, but then he came home to Canada and went into the civil service in order to work on public health issues, including TB. Public health held none of the prestige (not to mention compensation) of neurology and I had always wondered why he chose it.

But when I think of one in seven people, I think of a class of 27 students I teach at the moment. In that class, about four people would die of tuberculosis if this were the late 19th century. In 1882, the same year Koch identified the bacillus, Bryce joined the civil service in Ontario and started working on the first public health code in Canada – a document designed to reduce such death tolls.

When Peter Bryce reported on the appalling health conditions in the Indian Residential School system in 1907, most of the deaths were caused by TB. By then, in most of Canada the death rate due to tuberculosis had been reduced dramatically. But in the IRS system nearly one-quarter of all children would die or were dying of TB. When the story broke in the Ottawa Citizen on November 15, 1907, the headline was Schools Aid White Plague – white plague being a popular description of tuberculosis at the time.

Tuberculosis impacted Peter Bryce throughout his life. A note in my family tree says that Peter’s sister Katherine died of TB in 1876 at the age of 17. Further, Bryce’s son Henderson died of TB on December 31, 1931 at the age of 42. Henderson was the only one of Peter Bryce’s six children who went into medicine. After graduating from the University of Toronto with his medical degree, Henderson went to Haida Gwaii and worked as a doctor in Port Clemons and later at Stave Falls in the Lower Mainland where a huge hydroelectric dam was being built. Later, he did a residency in surgery at the University of Chicago and became the head of surgery at Vancouver General Hospital before discovering he had TB.

Dr. Henderson Bryce, ca. 1914

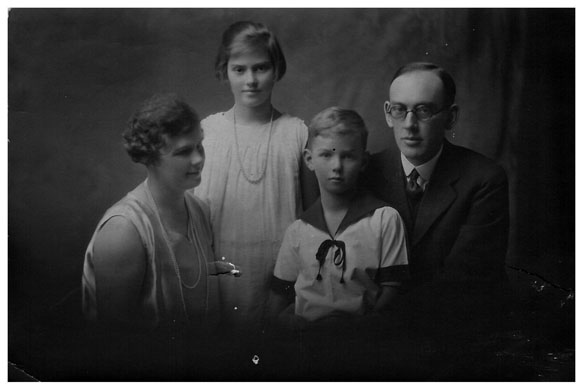

This is where the story gets personal for me, because Henderson was my grandfather and this is my family’s story. Granddad found out that he had TB sometime after my Aunt Helen was born in 1916. At the time, wisdom was that he would have a better chance of surviving if he moved to a drier part of the world, and so Henderson took a locum assignment in Princeton B.C., where my father was born, before settling in Kelowna in 1920. It seems Henderson was in remission for much of this time, because he worked at Kelowna General Hospital for a few years, but by the late 1920s, the TB had re-emerged, and he was dying.

Grandmother Jessie, Aunt Helen, my father Bill and Grandfather Henderson Bryce, 1927

A few years ago my Aunt Helen (who was 15 in 1931) told me she remembered taking the ferry up Okanagan Lake to meet her Uncle Bill, who had been sent by Peter Bryce (my Aunt called him “the old man”) to be with his brother, and to take the body back to Ottawa for burial. Shortly after my grandfather died on New Year’s Eve 1931, Uncle Bill transported his body back to Ottawa by train, arriving in time to hold a funeral service on January 9th.

A few days later Peter Bryce came home and told his family he was leaving to take a trip to the West Indies the next day. On January 12, he got on the Empress of Australia at New York City, and two days later on January 14, 1932, Peter H. Bryce died in his cabin, alone.

It is a tragedy that a man who did so much for so many, died alone at sea with the knowledge that the very disease he had spent his life fighting, had killed his son. But for me the real tragedy is that my father lost his father at the age of 13, and moreover watched his father die so slowly and painfully. The ravages of TB have the power to reach across generations, as so many in the Indigenous community know all too well.

A 15-year-old Canadian girl died of tuberculosis in January this year. Her name was Ileen Kooneeliusie and she was from the hamlet of Qikiqtarjuag in Nunavut. Andre Picard in the Globe and Mail writes about her death and the high prevalence of TB in the territory (in the interests of giving credit where it is due, the story was first told by Nick Murray of the CBC). In Canada, 4.7 people out of every 100,000 die of tuberculosis. In Nunavut, the rate is 229.6 per 100,000. It’s a disease that can be stopped, but early detection is a key, and Picard notes that this child’s death was caused by cultural and language differences

The mother of Ileen Kooneeliusie said that the principal barrier to getting care for her daughter was an inability to communicate the severity of her condition – because none of the nurses at the clinic spoke Inuktitut. She was not taken seriously. The language gap, and the condescension of health workers from away, have consistently been identified as an impediment to care in Nunavut and other Indigenous communities.

Peter Bryce would not be surprised.

At the Bryce family plot in Beechwood cemetery

The documentary film Finding Peter Bryce is currently in post-production but it needs funding to be completed. If you are interested in contributing, you can give through our partners, the Canadian Public Health Association and receive a tax receipt in return. Go to How to donate to the Film to find out more. Click here to see the promotional trailer. If you have other questions, suggestions or thoughts, please contact me at andyj.bryce@gmail.com