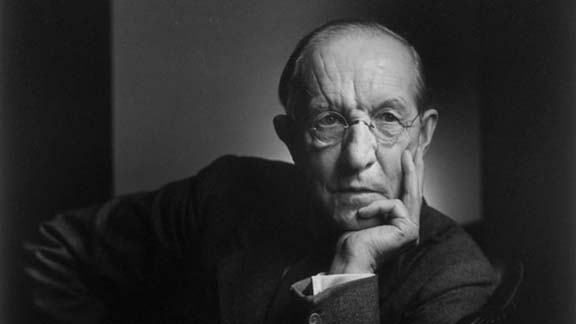

It is easy to stand back from the story of Peter Henderson Bryce, and wonder just what all the fuss is about. After all, as my second cousin David put it, “He was only doing his job.” It is the summer of 2014, the day after a Bryce family reunion where I had met dozens of other descendants of Peter Bryce – people I didn’t even know existed just a few months before. We are sitting around the remains of breakfast when the topic comes up. In today’s context, the actions of Peter Bryce seem relatively innocent; he was asked to go out and report on the conditions in residential schools and make recommendations to the government about a course of action, and that’s just what he did.

A year after that breakfast, Peter Campbell and I are interviewing Marie Wilson at a ceremony to unveil a plaque in Peter Bryce’s honour at Beechwood Cemetery in Ottawa. Her very presence at the ceremony means that indeed there was something very special about what Peter Bryce did.

“What is heroic about doing what you should be doing?” asks Wilson. She was one of three commissioners on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. She heard thousands of hours of testimony from residential school survivors, and read over the information and evidence gathered by the Commission. “What is heroic about doing the right thing? What is heroic about practicing your profession to the best standards you have sworn your career to?

“It’s heroic because the circumstances and the political framework of the day would not allow him to do the normal right thing,”

Dr. Adam Green agrees; in the late 1990s he was working on his Masters’ degree at Queen’s University when he ran across Peter Bryce.

“I am looking in one class at the early Canadian labour movement; I’m in another looking very much at what is called state formation in the early 20th century. Ultimately in doing research for two different papers, I come across Peter Bryce and this is because on one hand he is producing material on immigration and manpower, and on the other hand he is also working on the Aboriginal file,” says Green. We are interviewing him in the dining room of his suburban Ottawa home. Now Adam Green is a researcher for the federal government who also teaches courses in history at the University of Ottawa. All around us, just out of camera shot, are high chairs and kids’ toys. His life has moved on since researching and writing about Peter Bryce, twenty years ago.

“I was shocked that I actually found somebody who was perfectly at the centre of all of this,” says Green. “From a very human angle he’s turning science into something that is debunking every major myth you can think about in the early 20th century. “

Adam Green’s thesis Humanitarian, M.D.: Dr. Peter H. Bryce’s Contributions to Canadian Federal Native and Immigration Policy, 1904-1921 is probably the most comprehensive look at Peter Bryce available today, and I was lucky enough to find it on my first search. I clearly remember the winter evening I spent reading the thesis, and waking up a few nights later to refer to it, because something in the thesis had infiltrated my dreams. I am thrilled to be interviewing him.

“As much as he’s being scientific about it, he’s being very human and saying ‘forget about all of the myths and urban legends, here’s what the hard evidence tells me,’” says Green. “’The evidence tells me that Aboriginals are not by their nature unsanitary, and new immigrants from the steppes of Russia are not unsanitary.’ So while he’s delivering cold hard facts, he’s also flying in the face of what the commonsense knowledge was of new immigrant populations and of Aboriginals and it would be the reverse of what almost every Canadian thinks at the time.”

As we pack up at Adam’s house I remember my parents’ lessons about integrity: “Don’t follow the crowd. Do the right thing. Stand up for yourself.” I chat with Adam and help move equipment before driving to our next interview. It is a pretty normal scenario, one I’ve played out dozens of times. But on the inside I feel different; I feel like now I am more complete. Now I know where those lessons came from.

The documentary film Finding Peter Bryce is currently in post-production but it needs funding to be completed. If you are interested in contributing, you can give through our partners, the Canadian Public Health Association and receive a tax receipt in return. Go to How to donate to the Film to find out more. Click here to see the promotional trailer. If you have other questions, suggestions or thoughts, please contact me at andyj.bryce@gmail.com